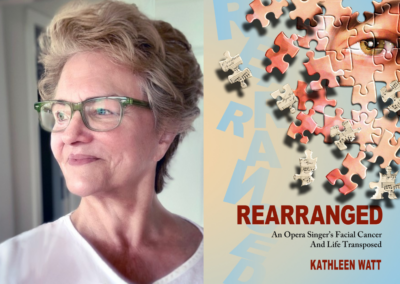

How did your treatment proceed?

I had elected to be reconstructed with tissue grafts from my own body, in a high-stakes procedure which was new then, but brilliant, and to me, worth the risks. Ultimately the odds broke the wrong way for me, and my reconstruction flat-lined, leaving me with lots of wounds to heal, hopefully in time for meaningful chemotherapy.

Barely a week after I was discharged from the hospital the intraoperative biopsy came back positive for cancer. Moreover, this biopsy revealed a more aggressive pathology. Instead of medium-grade chondrosarcoma, the labs showed osteogenic sarcoma in a high-grade tumor. Doctors immediately readmitted me to carve deeper margins into my nasal wall and eye socket. Meanwhile the window to begin my chemo course was closing.

All remaining maxillary hardware was removed, with some bone grafts still attached. Within three months of my initial tumor resection, still prior to chemotherapy, I’d undergone nine surgeries. By mid-September, almost nothing remained of my state-of-the-art facial reconstruction. I would have to be fitted for an oral prosthesis.

When my chemotherapy finally began in October, I wanted assurance that chemo would not destroy any more of me than necessary. So, I followed a referral to a trusted outside consult, and discovered that one component of my protocol, cisplatin, could potentially damage my hearing. I was seized with a spasm of patient advocacy. As my return to professional singing steadily faded, it became less and less relevant as a rationale for treatment. But wasn’t I steward of what body parts I had left? I couldn’t let go of my hearing without a fight.

In the end, my oncologist was able, somehow, to rebalance my chemo cocktail to sharply limit my intake of cisplatin.